Violence in Early and Late Adolescence[1] is part 3 in a series of blogs on Violence in Childhood by Dr Susan Bissell and Mohammed Alshurafa

As a child grows up, the types of violence they may experience, the context in which violence occurs, and the consequences of experiencing violence change. Older children and adolescents are not only experiencing violence in the forms of corporal punishment in homes or bullying online and at school, but they are also exposed to it in public spaces and communities. Their age also makes them more likely to be recruited into armed conflicts by political factions or to be used by criminals and cartels for different purposes such as human trafficking, drug dealing, and prostitution.[2] In general, adolescents are vulnerable to all forms of violence, yet the most prevalent form of violence is physical violence perpetrated by a member of their peer group.[3]

UNICEF’s report “A Familiar Face: Violence in the lives of children and adolescents” sheds light on some key facts of violence facing adolescents:[4]

- An adolescent is killed by violence every seven minutes. Just in 2015, violence took the lives of around 82,000 adolescents globally.

- Nearly 130 million (slightly more than one in three) students between the age of 13 and 15 experience bullying worldwide.

- As children grow from the early and middle childhood stage to early and late adolescence, the likelihood of being murdered from violent acts more than doubles.

- Worldwide, around 15 million adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 have experienced forced sex.

- Based on data from 30 countries, only one percent of adolescent girls who have experienced forced sex reached out for professional help.

The report also reveals the distinct patterns of each region’s leading cause of death among adolescents.

The United States: in 2015, the homicide rate among non-Hispanic Black adolescent boys in their second decade was almost 19 times higher than the rate among non-Hispanic White adolescent boys. If this rate was applied nationwide, the United States would be among the world’s top 10 most deadly countries.[5]

Middle East and North Africa (MENA): While only about six percent of the world’s adolescents live in the MENA region, more than 70 percent of adolescents who died in 2015 due to collective violence were living there. The number of deaths and mortality rate among this age group is 29.9 per 100,000. If adolescents worldwide faced the same risk of being killed due to collective violence as those in the Syrian Arab Republic, adolescents’ global mortality rate would be every 10 seconds.

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC): This area is considered the most dangerous region for adolescents when it comes to the risk of dying due to homicide. Around 70 adolescents in LAC die every day due to interpersonal violence.[6]

Violence against children is not limited to physical harm. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.”[7] Yale scholar Dr. Bandy Lee takes that definition a step further. Drawing from her 2004 personal notes she suggests violence is:

“intentional or threatened human action, either direct or through structural neglect and diminution of others, that results in or has a likelihood of resulting in human deprivation, injury, or death, or contributes to the extinction of the human species.”[8]

The context and type of violence a child is likely to experience can vary depending on their gender, ethnicity, class, disability status, sexuality, and socioeconomic background. For example, using a gendered lens, psychological violence is more common against girls: 39.3 percent of parents reported using psychological violence against a female child in the past three months compared to 32.6 percent against a male child. On the other hand, severe physical violence was more common towards boys: 16.8 percent of parents reported using physical violence against a male child compared to 12.9 percent against a female child. While this data is specific to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the findings are similar to that seen in other parts of the world.[9]

Other factors can also influence the type of violence children are exposed to as they get older. For instance, disabled children might be more likely to experience bullying than children without disabilities. A study in the United States showed that students with disabilities in elementary, middle, and high school are 1.5 times more likely to be bullied than the national average for students without disabilities.[10]

Additionally, children living in war zones are more likely to experience armed violence. UNICEF writes, “There are over 61 million children living in countries affected by war in MENA out of a total child population of nearly 166 million. This is to say that over a third of children in MENA are affected by ongoing conflicts and violence. One in every three children.”[11]

Adolescents experience an increase in sexual assault, particularly for girls. In some countries, mainly in Africa, nearly 30 to 40 percent of adolescent girls become victims of sexual violence before turning 15 years old.[12] Looking at child sexual abuse from a gendered lens, around 90 percent of perpetrators are males. Victimization reporting rates among girls are two to three times higher than boys. In other contexts and organizational settings, victimization of boys has been found to be higher than that of girls.[13]

Adolescents experience an increase in sexual assault, particularly for girls. In some countries, mainly in Africa, nearly 30 to 40 percent of adolescent girls become victims of sexual violence before turning 15 years old.[12] Looking at child sexual abuse from a gendered lens, around 90 percent of perpetrators are males. Victimization reporting rates among girls are two to three times higher than boys. In other contexts and organizational settings, victimization of boys has been found to be higher than that of girls.[13]

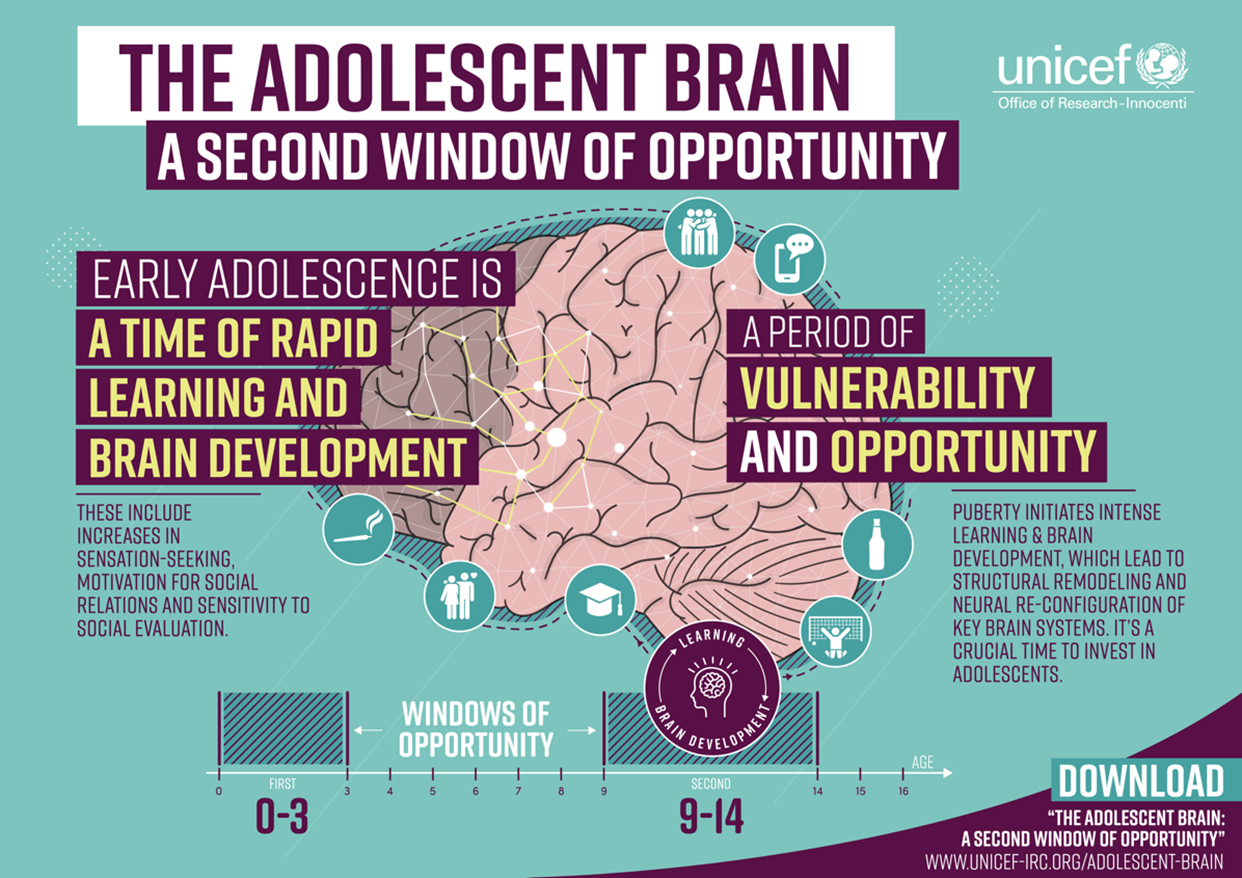

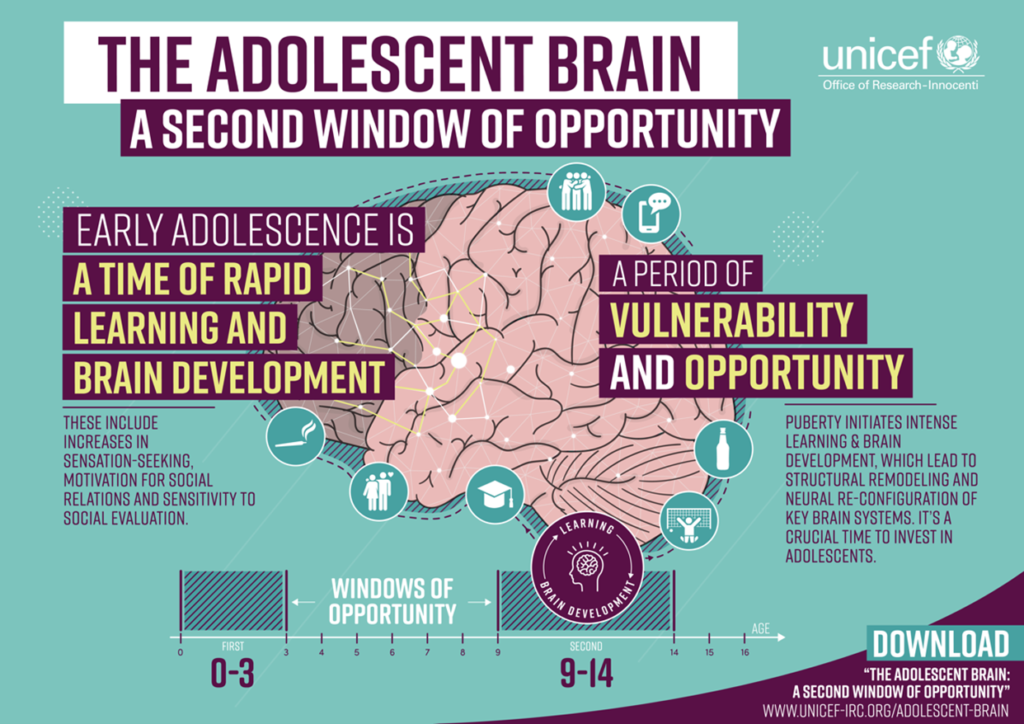

Given that children in their second decade are so vulnerable, interventions are needed to ensure their safety and attainment of their full developmental goals. In a UNICEF report The Adolescent Brain: A second window of opportunity, eight experts in Adolescent Neuroscience and Development summarized their work’s findings. The report offers insights into how to maximize adolescents’ potential during this period. The publication also reveals that adolescents’ brains are still under the process of development, which offers a significant second chance for those who have experienced harm in early childhood.[14]

All this data suggests that efforts to prevent and respond to violence across the full expanse of childhood need to be mindful of significant differences in the causes and consequences of violence. Moreover, important characteristics, including but not limited to gender and ethnicity, will make real differences in the effectiveness of programs and interventions. One size most certainly does not fit all.

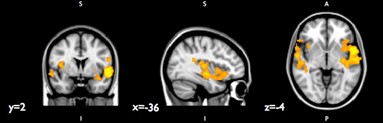

While undergoing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) has serious damaging effects on the brain’s architecture and long-term health,[15] research has also shown that exposure to community violence in early adolescence affects brain development. Both the amount of hippocampal volume and amygdala volume decreases when an adolescent is exposed to community violence.[16] Youth with smaller amygdala volumes have been linked to a risk of depression and behavior problems,[17] whereas smaller hippocampal volumes may indicate learning and cognitive difficulties.[18]

DARBY SAXBE/CC BY-ND — For adolescents who are exposed to higher community violence incidents, the right hippocampus showed stronger connections with other brain regions linked to emotion processing and stress.

Children across the spectrum experience violence differently. In fact, children in their adolescence are more likely to participate in violence prevention and protect themselves actively. In the communities where it has sites, Cure Violence Global (CVG) aids this participation and adapts its violence reduction health approach based on the dynamics of violence in the local community. In its work across the globe, CVG has engaged young people in the development of violence interruption, outreach services, and community reintegration.

In East Jerusalem through CVG’s West Bank project, a group of project participants are working to limit the spread of youth violence. Participants are implementing public education campaigns that aim to raise the understanding of violence as a health issue using accessible language. As part of this project, they are also conducting outreach workshops with young people aged 17-22 to raise their awareness about the contagious nature of violence and consult them in developing public education messages.

[1] Early adolescence might be broadly considered to stretch between the ages of 10 and 14, while Late adolescence encompasses the latter part of the teenage years, broadly between the ages of 15 and 19 (UNICEF)

[2] Sergio Aguayo. “Armed Violence Against Children in Central America” Interview by Jacqueline Bhabha. Harvard FXB Center for Health and Human Rights

[3] Shiva Kumar, A. K., Stern, V., Subrahmanian, R., Sherr, L., Burton, P., Guerra, N., … & Mehta, S. K. (2017). Ending violence in childhood: a global imperative.

[4] United Nations Children’s Fund, A Familiar Face: Violence in the lives of children and adolescents, UNICEF, New York, 2017.

[5] Calculated on the basis of data from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[6] United Nations Children’s Fund, A Familiar Face: Violence in the lives of children and adolescents, UNICEF, New York, 2017.

[7] World report on violence and health: summary. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002

[8] Lee, Bandy (2019). Violence: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Causes, Consequences and Cures. Oxford: John Wiley and Sons.

[9] Barker, G., & Nascimento, M. (2010). Violence against young children: What does gender have to do with it?. Early Childhood Matters, (114), 27-32.

[10] Blake, J. J., Lund, E. M., Zhou, Q., Kwok, O. M., & Benz, M. R. (2012). National prevalence rates of bully victimization among students with disabilities in the United States.

[11] Child Protection | UNICEF Middle East and North Africa. https://www.unicef.org/mena/child-protection

[12] UNICEF Annual Report 2014

[13] United Nations Children’s Fund (2020) Action to end child sexual abuse and exploitation, UNICEF, New York

[14] Balvin, Nikola; Banati, Prerna (2017). The Adolescent Brain: A second window of opportunity – A compendium, MiscellaneaUNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti, Florence

[15] Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinn, L., … & Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232-e246.

[16] Saxbe, D., Khoddam, H., Piero, L. D., Stoycos, S. A., Gimbel, S. I., Margolin, G., & Kaplan, J. T. (2018). Community violence exposure in early adolescence: Longitudinal associations with hippocampal and amygdala volume and resting state connectivity. Developmental science, 21(6), e12686.

[17] Pechtel, P., Pizzagalli, D.A. Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: an integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology 214, 55–70 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2009-2

[18] Noble, K.G., Tottenham, N., & Casey, B.J. (2005). Neuroscience Perspectives on Disparities in School Readiness and Cognitive Achievement. The Future of Children 15(1), 71-89. doi:10.1353/foc.2005.0006.