Part 1 in a series of blogs on Violence in Childhood by Dr Susan Bissell, Jule Voss, and Mohammed Alshurafa

The effects of childhood violence can last a lifetime.

With 1 billion children around the world experiencing some form of violence – 1 in 2 children – we have a serious problem on our hands.[i] 1 in 4 children under the age of five live with a mother who has been a recent victim of intimate partner violence.[ii] 3 in 4 are regularly subjected to violent discipline by their parents or other caregivers at home.[iii] Annually, 1 in 8 children are born in a conflict zone.[iv]

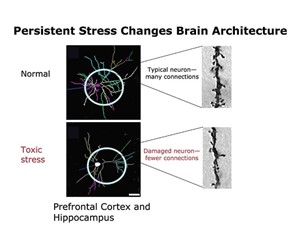

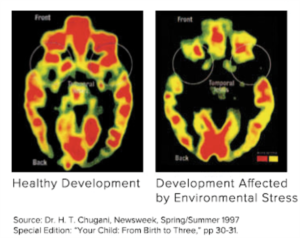

During the first five years of life, children undergo a rapid period of brain development. This lays the foundation for future educational attainment, physical and mental health, employment opportunities, and civic participation.[v] By age five, more than 90 percent of a child’s brain has already developed.[vi] When children experience intense or prolonged stress during early childhood, it alters their neurobiological pathways. This, in turn, is like to result in changes in regulatory systems that shape human responses to stress.

Brains subjected to toxic stress have underdevel oped neural connections in areas of the brain most important for successful learning and behavior in school and the workplace. Source: Radley et. al (2004), Bock et. al (2005). Credit: Center on the Developing Child.

Children often experience toxic stress because they have directly experienced violence, exploitation, abuse and/or neglect.[vii] Research has shown that children who experience one adverse child experience (ACE) become more likely to experience others. The effects of multiple ACEs are cumulative, meaning that as the number of ACEs increases so does the likelihood of negative outcomes in adulthood.[viii]

High levels of community violence can lead to toxic stress and cause harm to young children. Indeed, from the moment a child is born their experiences are influenced by two interrelated ecosystems. First, the individual experiences and relationships of the child form the basis of the child’s early development. This is the ‘microsystem.’ Social institutions – the ‘macro-system’ – are also formative. When social institutions such as schools, institutions of faith, and social settings for play and recreation are impacted by violence, it is little wonder that children, caregivers and families are personally and collectively suffering as a result.

The impacts of high rates of community-level violence are real and measurable. For instance, this violence is related to lower school attendance, higher rates of substance abuse, and increased feelings of insecurity and low self-esteem among children and adolescents. This holds true, even when controlling for other risk factors, such as poverty or racial disenfranchisement.[ix] Extended into adulthood, the direct and indirect consequences of violence against children worldwide are estimated to cost 7 trillion USD per year, or 8 percent of the global gross domestic product (GDP).[x]

A PET scan of a child’s brain developed normally compared to another child’s brain exposed to environmental stress.

Just as community violence is socially constructed, so too its prevention. Efforts are underway, the world over, to interrupt and cease outbursts and recurring violence within communities. In 1992, the murder of seven-year-old Dantrell Davis in the Cabrini-Green public housing development of Chicago helped spark a three year truce between rivial gangs to help keep children out of their crossfire. In 2020, local leaders are working to revive the agreement in the wake of multiple shootings involving children in the neighborhood. Meanwhile, in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, community leaders have been trained to identify and mediate potentially lethal conflicts in the community in order to prevent violent occurrences, thus shielding children and families. Community-based ‘disruptors’ of violence are able to diffuse violent events before they happen. Coming from within communities, these disruptors are outreach workers of integrity and have earned the trust of those they serve among.

Support for responsive caregiving[xi], income supplement programmes, early learning interventions and a host of other efforts supplement violence disruption. Social justice advocacy, law reform, and the strengthening of education and vocational training programmes are also integral to success. Finally, social norm change is at the heart of community-based violence prevention. Experience and evidence are clear – social norm change is an ‘inside-out’ process. It is sustained by internal drivers and local champions.

Just as the effects of violence can last a lifetime, so too can the effects of peace.

Dr Susan Bissell is a human rights advocate working as a Visiting Scholar and Senior Fellow at the FXB Centre for Health & Human Rights, T.H. Chan School of Public Health of Harvard University. Prior to this appointment, her thirty-year career with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) was centered on protecting the rights, safety, and security of children throughout the world. Dr. Bissell is a member of the Cure Violence Global Board of Directors.

Jule Voss is an undergraduate student studying Global Security and Justice at the University of Virginia and an intern with Cure Violence Global. She also serves as a member of the board of the NGO Action on Child, Early, and Forced Marriage where she has conducted research on child widows, gender-based violence, and unintended consequences of development and humanitarian programming.

Mohammed Alshurafa is the MENA Program Officer at Cure Violence Global. He responsible for the creation, oversight, and implementation of programming activities in the region.